Can Bayesian Analysis Save Paxlovid?

Posted onPaxlovid

Paxlovid is a new antiviral (protease inhibitor) that when paired with ritonavir provides excellent protection against hospitalization for those patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Pfizer, the manufacturer, had two endpoints. The first endpoint was for “High Risk” patients and a secondary endpoint for “Standard Risk” patients. I thought it was neat that BioNTech/Pfizer used a Bayesian analysis for their BNT162b2 vaccine and was a little surprised when I saw a frequentist p-value for their second endpoint:

From their press release.

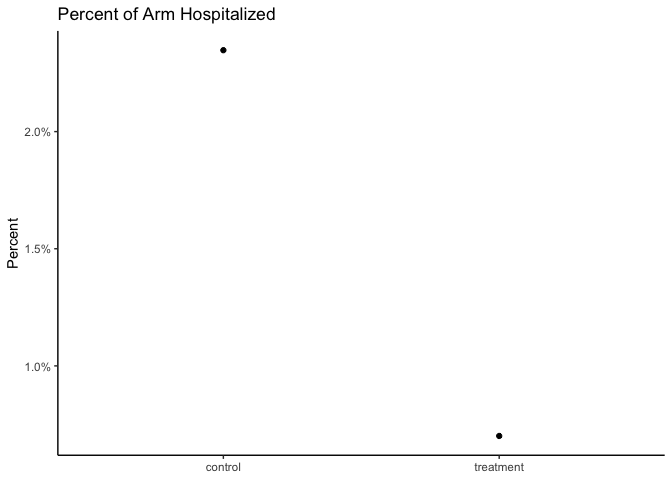

A follow-on analysis at 80% of enrolled patients was consistent with these findings. In this analysis, 0.7% of those who received PAXLOVID were hospitalized following randomization (3/428 hospitalized with no deaths), compared to 2.4% of patients who received placebo and were hospitalized or died (10/426 hospitalized with no deaths); p=0.051.

Oh no, p < 0.05, let’s throw away the drug for standard patients. This seems like a perfect time to do a Bayesian analysis and see what our uncertainty could be regarding the effect in this seemingly underpowered arm of the trial (e.g., we would have liked to have seem more people in this cohort because the smallest reasonable effect we would like would be say a 20% reduction in relative risk or even less as our hospitals fill with patients).

Reanalysis

First we need to recreate the data:

dat_trials <- tibble:: %>%

dat_trials %>%

+

+

+

+

Seems like there is an effect! We can also reproduce the frequentist analysis:

2-sample test for equality of proportions with continuity correction

data: c(3, 10) out of c(428, 426)

X-squared = 2.8407, df = 1, p-value = 0.04595

alternative hypothesis: less

95 percent confidence interval:

-1.000000000 -0.000353954

sample estimates:

prop 1 prop 2

0.007009346 0.023474178

Ok, so p < 0.05 in this is weird. Maybe they did some multiple testing adjustment? Moving on….

Enter Stan

I am going to use the following Stan code that was posted on this blog which in turn originated from this blog.

Nothing too crazy, it this code, it just fits our observed data to binomial distributions and we can look at the relative effect and the absolute effect

//based on https://www.robertkubinec.com/post/vaccinepval/

// Which is based on https://rpubs.com/ericnovik/692460

data {

int<lower=1> r_c; // num events, control

int<lower=1> r_t; // num events, treatment

int<lower=1> n_c; // num cases, control

int<lower=1> n_t; // num cases, treatment

array[2] real a; // prior values for treatment effect

}

parameters {

real<lower=0, upper=1> p_c; // binomial p for control

real<lower=0, upper=1> p_t; // binomial p for treatment

}

transformed parameters {

real RR = 1 - p_t / p_c; // Relative effectiveness

}

model {

(RR - 1)/(RR - 2) ~ beta(a[1], a[2]); // prior for treatment effect

r_c ~ binomial(n_c, p_c); // likelihood for control

r_t ~ binomial(n_t, p_t); // likelihood for treatment

}

generated quantities {

real effect = p_t - p_c; // treatment effect

real log_odds = log(p_t / (1 - p_t)) - log(p_c / (1 - p_c));

}

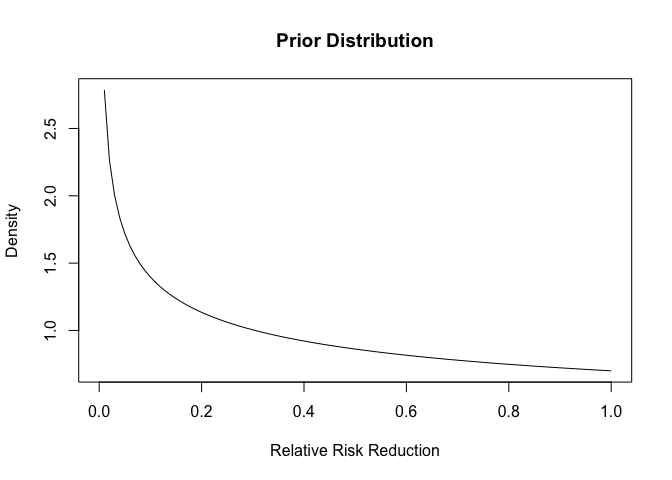

Additionally, we need to supply a prior. I am going to use exactly the same priors that Pfizer/BioNTech for their vaccine as a starting point:

This distribution places more density on the drug not having an effect, so we are being a bit pessimistic.

Run the Code

mod <-

dat <-

fit <- mod$

Analyzing the Results

First we can look at our summaries (note that I did look at the chains for mixing and we have adequate samples in the tails).

fit$ %>%

%>%

knitr::

| variable | median | mean | q5 | q95 | rhat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lp__ | -74.10 | -74.41 | -76.36 | -73.47 1 | |

| p_c | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 1 |

| p_t | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 1 |

| RR | 0.68 0 | .63 | 0.21 | 0.89 | 1 |

| effect | -0.02 | -0.02 | -0.03 | 0.00 | 1 |

| log_odds | -1.16 | -1.19 | -2.25 | -0.25 | 1 |

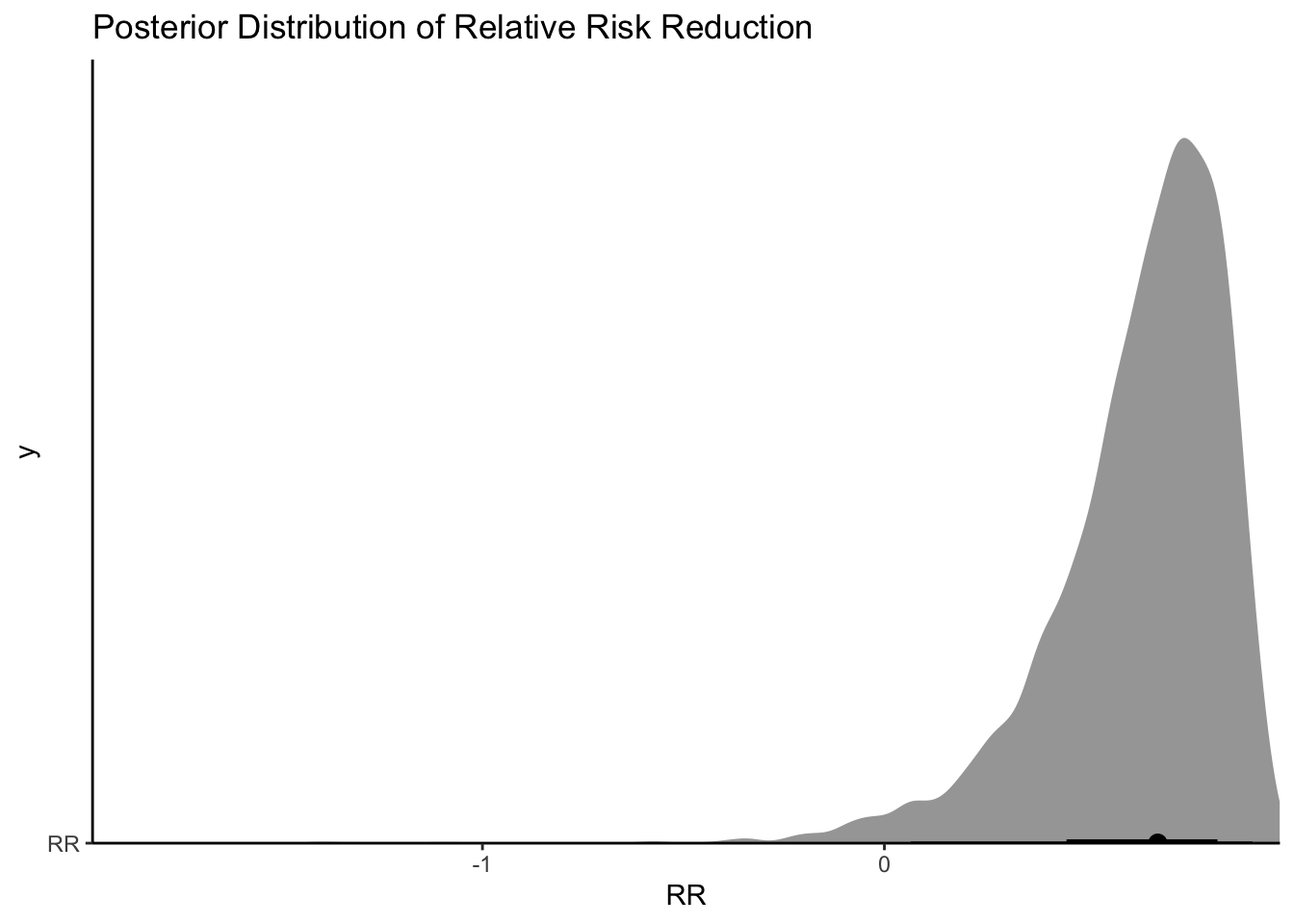

So it seems like there is evidence of an effect (a relative risk reduction of 20-89%)!

draws <- fit$ %>%

draws %>%

#median_qi(VE, .width = c(.5, .89, .995)) %>%

+

+

+

+

+

Ok, so looks again like the bulk of the posterior distribution is a positive effect. If I said I were only interested in a drug that had a 30% relative risk reduction, I could do the following:

[1] 0.921

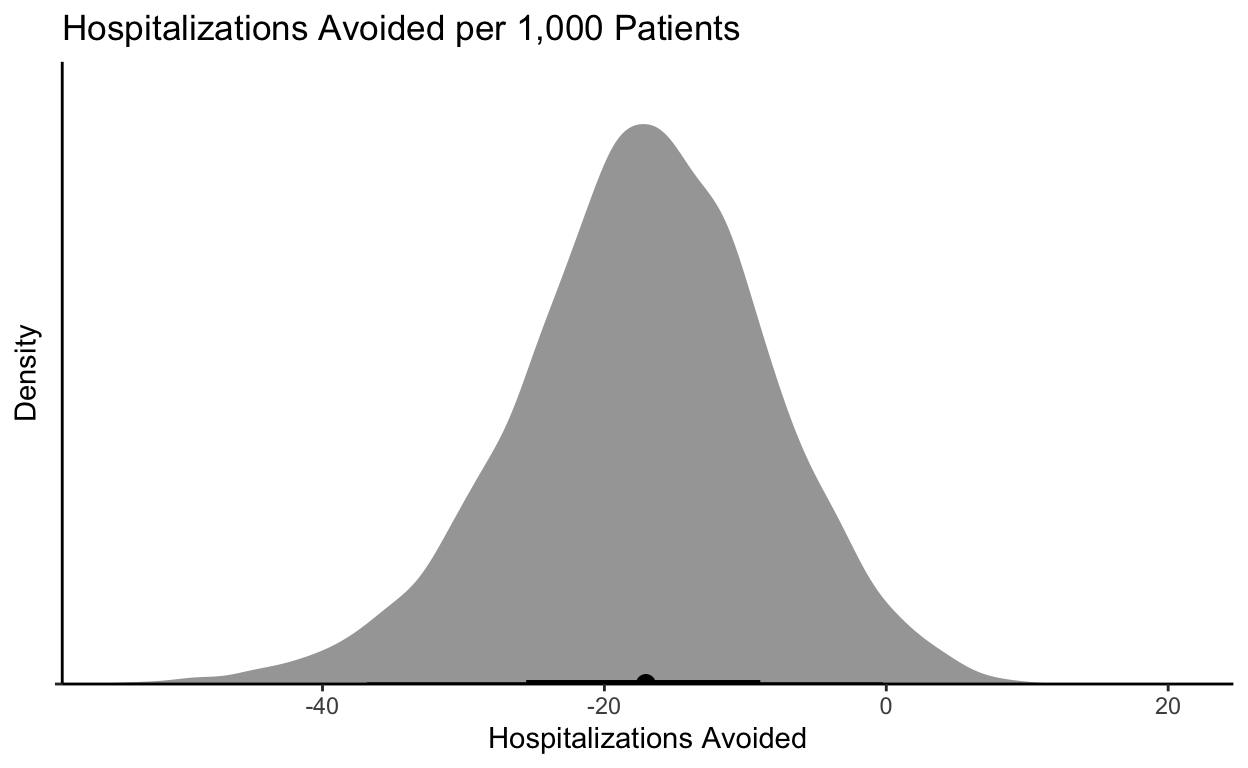

Ok so 92% isn’t bad! In the middle of a pandemic with patients appearing (with standard risk factors) and an oral treatment option, I would take that probability. I could also look at what the absolute effect would mean on hospitalizations:

draws %>%

+

+

+

+

+

If I could prevent 0-40 hospitalizations with a cheap-ish treatment, I would take it. A reminder that if I admit 20 patients and they each stay 4-5 days, I have tied up a ton of “bed days.”

Summary

The important point here is the Bayesian analysis provides a way to do these kinds of analysis and not throw away data when endpoints are not met. In this case the “standard risk” patients would likely profit from the drug.

Citation

BibTex citation:

@online{dewitt2021

author = {Michael E. DeWitt},

title = {Can Bayesian Analysis Save Paxlovid?},

date = 2021-12-15,

url = {https://michaeldewittjr.com/articles/2021-12-15-can-bayesian-analysis-save-paxlovid},

langid = {en}

}

For attribution, please cite this work as:

Michael E. DeWitt. 2021. "Can Bayesian Analysis Save Paxlovid?." December 15, 2021. https://michaeldewittjr.com/articles/2021-12-15-can-bayesian-analysis-save-paxlovid